- Parish news

From the Historian: Giving thanks for George Middleton and the Black, Gospel witness

As our nation remembers the ministry of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr, we at Trinity Church gratefully recall the Black witness to the Gospel in Boston and in our parish. With thanks, we share this reflection about George Middleton, a parishioner of Trinity Church in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth Centuries.

Dear Trinity Church and friends,

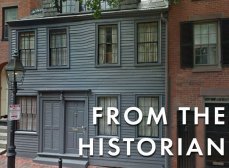

It still stands today, a two-family wood frame house, constructed between 1786 and 1787. It is considered the oldest surviving residence in Boston’s Beacon Hill. George Middleton and Louis Glapion built the house, two Black men whose families worshipped at Trinity Church. They belonged to a dynamic community of free people of color living and working in the neighborhood’s North Slope. In this dwelling they raised their families and welcomed the camaraderie of others fighting for the rights of Boston’s Black citizens.

Born circa 1735, George Middleton was baptized “a free Negro an adult” at Trinity Church in 1781, the same year that he married Elsie Marsh. She was baptized the following year. Between 1783 and 1795, Middleton’s children Alice, George, Joseph and James were baptized. Middleton himself would serve as a witness at the baptism of at least seven adults of color between 1788 and 1791. Church records note his wife's death in 1795 and that of his sons James and George in 1800 and 1801.

A skilled horse trainer by profession, Middleton at one time worked as a coachman for ropemakers George and Peter Cade. In his personal life Middleton was an activist. During the Revolutionary War, Middleton led the Bucks of America, a group of African American soldiers based in Boston tasked with protecting local goods and property. John Hancock, the first governor of Massachusetts, commemorated the company’s service with a presentation to Middleton of a white silk flag painted with the initials J.H. (John Hancock) and G.W. (George Washington).

He was an early member of the African Lodge of Freemasons, a socially and politically active fraternal organization founded by Prince Hall. In 1796 he helped organized the African Benevolent Society, an institution organized to help African Americans, especially widows and orphans, through job placement and financial relief. After the death of Prince Hall, and after his successor Nero Prince departed for Russia, in 1809, George Middleton was appointed the African Lodge’s third Grand Master. By this time Middleton had lived for over seven decades. He had fought for the freedom of a new nation and until the end of his days would often be referred to as “the Colonel.” Though slowed by age, he remained a man of fiery conviction so when the Belknap Street riot occurred, he stood his ground.

Middleton’s home was located at 5 Pickney Street not far from the intersection of Belknap Street (now Joy Street). Each year for several years, Black people in Boston celebrated on Boston Common the abolition of slavery in Massachusetts. As abolitionist Lydia Maria Child recalled,

“Our negroes, for many years, were allowed to peaceably celebrate the end of the slave trade; but it became a frolic for the white boys to deride them on this day, and finally, they determined to drive them, on these occasions, from the Common. The colored people became greatly incensed by this mockery of their festival, and this infringement on their liberty, and a rumor reached us … that they were determined to resist the whites, and were going armed, with this intention. … Soon terrified children and women ran down Belknap Street, pursued by white boys, who enjoyed their fright. … clubs and brickbats were flying in all directions. At this crisis, Colonel Middleton opened his door, armed with a loaded musket and, in a loud voice, shrieked death to the first white who should approach. … Colonel Middleton’s voice could be heard above every other, urging his party to turn and resist to the last.”

In the end, it appears that two white men, including Lydia Maria Child’s father, David Francis, managed to quell the crisis, one calming the white leaders and Francis, who lived near Middleton, beseeching his neighbor to stand down. According to Child, Middleton, in tears, did so, handing her father his musket and reportedly saying the words, “I will do it for you, for you have always been kind to me.” And then he retired into his home and shut his door upon the scene.

But he did not shut his door to making change.

Middleton focused his attentions on Black children and the school system. He fought to secure financial support for Black schools while challenging the notion of segregated schools. Before city committees he pleaded for school reform and equality.

George Middleton died in 1815. He left a profound legacy that others would build upon. Obituaries appeared in numerous papers. They all made note that he was "a respectable man of color." He was 80 years old.

The Collect for Martin Luther King, Jr, Pastor and Martyr

Almighty God, by the hand of Moses your servant you led your people out of slavery, and made them free at last: Grant that your church, following the example of your prophet Martin Luther King, may resist oppression in the name of your love, and may strive to secure for all your children the blessed liberty of the Gospel of Jesus Christ; who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and for ever. Amen.

Until next month,

Cynthia Staples

Sources:

-

Ritz, Erin, Joshua Kirwan, and David J. Trowbridge. “George Middleton House (Black Heritage Trail Site 2)” https://theclio.com/tour/178/10

-

Lydia Maria Child recounts this episode from her youth in William Cooper Nell, The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution (Boston, 1855), pp 24-27.

-

A Question of Manhood: A Reader in U.S. Black Men's History and Masculinity, Vol. 1: "Manhood Rights": The Construction of Black Male History and Manhood, 1750-1870 (Blacks in the Diaspora) (Volume 1) by Darlene Clark Hine and Earnestine Jenkins

The image is of the house at 5 Pinckney Street in Beacon Hill. It is taken from Google Street View, 2011.