- Vested Interest

Gotta Catch 'Em All

I.

I spent last week in the wilderness.

This isn’t a metaphor—I was camping on the Georgian Bay in Northern Ontario, a three-hour motorboat ride from the nearest harbor. My father and I spent much of our time fishing, trolling for smallmouth bass in the clear cold waters of Lake Huron. It seems so remote, so empty up there. The landscape is all peach granite and blue water and gnarled pine, lichen and blueberry bushes, and nothing seems to move except the restless tossing of tree branches in the wind and the rhythm of the waves, and you in your tiny, frail-seeming outboard motorboat, wandering in and among the wave-smoothed rock islands. You are alone in a desolate landscape.

Suddenly, you feel a tiny twitch come down the length of the fishing rod into your palm. And if you’re lucky, it’s not weeds or rocks but a fish, and you find yourself connected with a fine taut thread to a beast that is astonishingly strong for its size, flexible, unpredictable, and fighting for its life. You look down into the flickering blue water and see, not just the fish you’re trying to catch, but others, maybe half a dozen. They are shadowy, graceful, alien.

Or maybe the fish aren’t biting, and instead your eyes wander and you see a flash of movement. Maybe it’s a great blue heron, or an osprey. Maybe it’s a delicate brown mink trotting over the rock. Maybe it’s even a black bear lolloping back into the trees. You realize, though, that this landscape isn’t desolate. It’s teeming with life, right down to the indignant little crayfish snapping their pincers under every rock. And this life is not human. It is wild.

II.

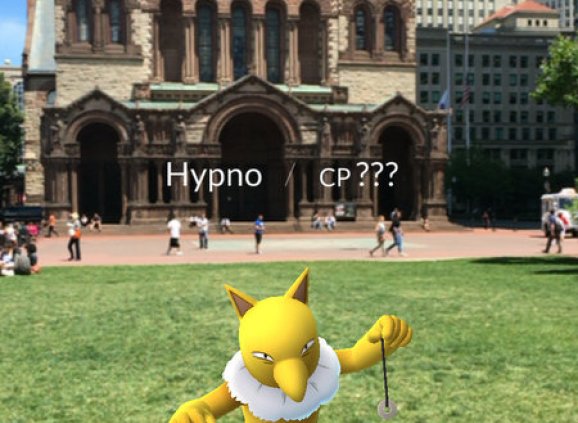

Today I discovered that while I was gone, Pokémon Go had taken over the internet. This app version of the popular video game franchise allows people to immerse the wild, hungry, curious little digital demons called Pokémon into the world we inhabit. You walk through your neighborhood, meeting beasties, capturing them, and, over time, training and nurturing them until they develop into bigger, stronger beasties. Through your smartphone’s camera, you can see Pokémon apparently interacting with the real world, hanging out in your office, or on your street, or in the Copley Square farmer’s market. You must venture into the outside world to play this game: certain Poké hatch from eggs which germinate only when you walk around; and Pokémon congregate at gyms where players can meet other players face-to-face and have their Pokémon do battle.

There is a primal allure to all this—no wonder Pokémon Go has surpassed Tinder in popularity and is gaining rapidly on Twitter. To discover that your quotidian world is, after all, alive! To discover and catalogue and tame a whole host of mysterious creatures! To be transformed into an explorer, scanning the world around you for invisible creatures! Some of them are friendly, some of them are vicious—you won’t know until you interact with them. But they are there, moving just at the corner of your eye. It reminded me of the hours I spent as a child building a “bird trap” consisting of a box propped up with a stick, with birdseed underneath it. My plan—which, thankfully, never panned out—was to wait until a bird came to take the seed, pull the string attached to the stick, and trap the bird underneath. Then I would tame it, and it would return from its flights afar to sit on my shoulder. I wanted to capture a little of that wildness in my world. I wanted to connect with life that was beyond my grasp.

III.

This reminds me, as so many things do, of being in church. I think back to the spring, and Kirsten Cairns’ extraordinary staging of Benjamin Britten’s The Company of Heaven at Trinity. It’s a choral production that draws on scripture, poetry, and folklore to tell the stories of angels—those supernatural beings who, our tradition tells us, hover all around us, mysterious but by no means unreachable. It’s impossible to describe the experience of being in the massive, soaring darkness of Trinity while these stories were told. Gabriel greeted Mary; the angel called to Elijah; God’s angelic forces battled Lucifer’s and cast them into the pit of fire. And for me it was as though Trinity’s tower were blown off, and the wildness that hovers outside my ordinary world were made manifest. As though my shoulder were just lightly brushed by a feathered wingtip.

We don’t have much time these days for stories about angels and demons, and maybe that’s a mistake. Somehow we as a church have bought into the mindset of materialism so much that it feels gauche and childish to discuss these things. Of course angels aren’t real, right? Of course demons aren’t real. They’re superstitious fantasies, fairy tales. If our God-talk is going to be taken seriously, we need to hold such superstition at arm’s length. And so we’ve taken these stories out of our conversations about God and transferred them to our pastimes: fantasy novels, sci-fi, comics, video games, movies. (I find it fascinating and entirely appropriate that many Pokémon characters are based on myths and legends from around the world.)

Don’t get me wrong: I downloaded Pokémon Go. I said it was “for work,” but really it’s because it looked awesome. Fantasy and sci-fi literature formed me and in many real ways saved me as a child and teen. I love all things that allow us to be playful and curious about the world around us, and I love that these “childish” pastimes are overrunning “adult” pursuits. The nerds and dreamers have won! But I wish we the church could reclaim our willingness to play with things that defy categories of real and unreal. Have you ever read Paradise Lost? Religion pretty much invented world-building! Milton (whom I defy anyone to call unsophisticated) didn’t waste his time muttering self-deprecatingly that Lucifer and Raphael weren’t really real. He knew that they mattered. They still matter. We still need them.

More than this, when you move something into the category of religion you allow it to be important, even desperately so. When engagement with the wild life of our imaginings becomes categorized as a pastime, a game, it’s hard to make the case for its importance. And we as a culture are just terrible at understanding that things that aren’t materially observable actually matter, that symbols carry weight, that the stories we tell have consequences.

So then, back to Pokémon, this world of charming and malevolent little demons, and back to the title of this piece: Gotta Catch 'Em All. What do you do, in the world of Pokémon, when you find something alive and alien, something wild? You catch it, and you lock it into a tiny ball, and you stash it safely in your avatar’s backpack. You trap it and control it and use it for your own purposes. How…sad. We’re cultivating an awareness that the world contains mysterious wonders, in order immediately to tame them. Like my childhood self, crouching uncomfortably under a bush waiting to trap a bird, the game asks us to respond to wildness with that first, grasping impulse: Make it mine. But like that imaginary tethered bird, or (alas) like the fish we ate every night for dinner, if we succeed in taming what is wild we thereby destroy it.

Is this farfetched? Taking a game too seriously? Maybe—but as we in the church know, the stories we tell do have consequences. They make us into who we are. And so I’d rather tell stories of demons and angels, who are in my purview but never in my total control. I’d rather find ways to open my eyes to the life all around me, unsnag the hook and watch the fish swim back into the flickering deep.

At "Vested Interest," church nerd Mary Davenport Davis explores all things liturgy and music at Trinity and beyond. Chime in with comments and questions!

Comments