Dear Trinity Church and friends,

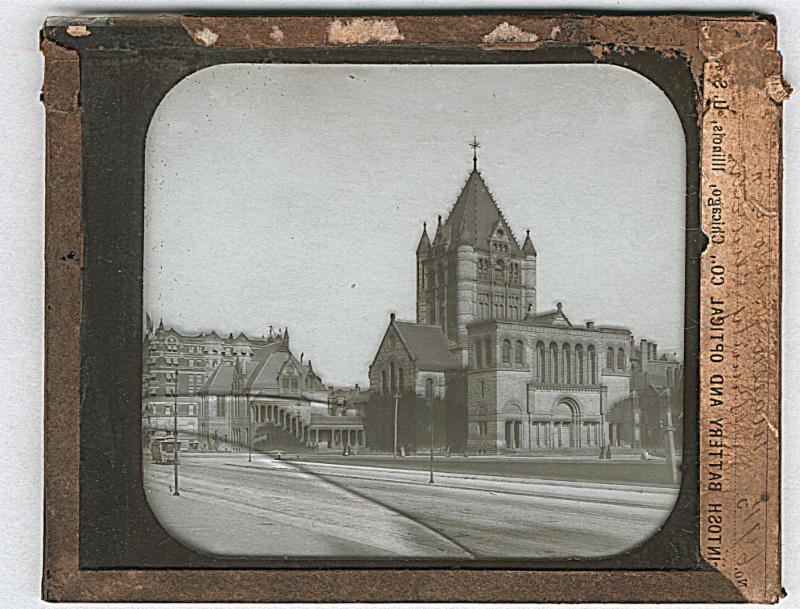

Elijah Winchester Donald preferred the monicker E. Winchester Donald. As the tenth Rector of Trinity Church, called to serve in October 1892, he followed in the footsteps of his friend, Phillips Brooks, the prior rector of Trinity who had been selected as Bishop of Massachusetts earlier that same year. Just three months later Brooks unexpectedly died. An immense vacuum was felt not only at Trinity but across Boston and beyond. Reportedly, at some point Donald took a deep breath and said, “Well, someone has to step into the breach.”

Throughout his career as clergy Donald was known for being forthright, compassionate, and a man of action. He grew up in a household and community where people acted upon their faith and their beliefs. Donald was born in 1848 in Andover, Massachusetts. He was of Scottish heritage. His father, William C. Donald, was a successful ink manufacturer. His mother’s name was Agnes. His parents influence would profoundly shape Donald. In 1846 when local Andover churches refused to denounce slavery, his parents were among the people who broke away to organize Andover’s Free Christian Church. His father once recounted, “We banded ourselves together and took counsel of one another and of God as to how we could honor Him and do something for the liberation of three million of our brethren held in slavery in the South. After much prayer and conference, we came to the conclusion that we must come out from the other churches that apologized for slavery and received slaveholders into their communion. … we were organized with the Rev. Elijah Carpenter Winchester as our leader and pastor…”

Donald graduated from Amherst College, and in later years, would serve as a Trustee. He was also the first Episcopal clergy to receive an honorary degree of Doctor of Divinity at the school. He did not immediately seek to become a priest. Instead, after Amherst, he first worked as a teacher and then as a journalist before attending divinity school in Philadelphia and then Union Theological Seminary of New York.

In 1882, after serving as an assistant priest, Donald was called as rector of Church of the Ascension in New York where he served for ten years before coming to Trinity. At Church of the Ascension, he was noted as an orator but even more so for his hands-on approach to outreach ministries. His approach fostered a sense of welcome such that the pews of the church were filled with a diverse cross section of the community. Once at Trinity, as Brooks had done before him, Donald continued to welcome all into the pews and nurtured the church’s outreach ministries, both near and far.

He served as rector at Trinity during an important time in U.S. history. The nation grappled with what had been deemed “the Negro problem.” How to support and “raise up” the millions of Blacks freed from enslavement and their offspring. The key to the uplift of Blacks was thought to be, as it had been even before the Civil War, education. But not just any education. There were those, and Donald was among them, who thought liberal arts was important but southern Black people needed to develop life and trade skills to be self-sufficient whether in agriculture or banking. Also important was the education of a cadre of Black teachers. Schools to train teachers and teach trades existed but they needed support.

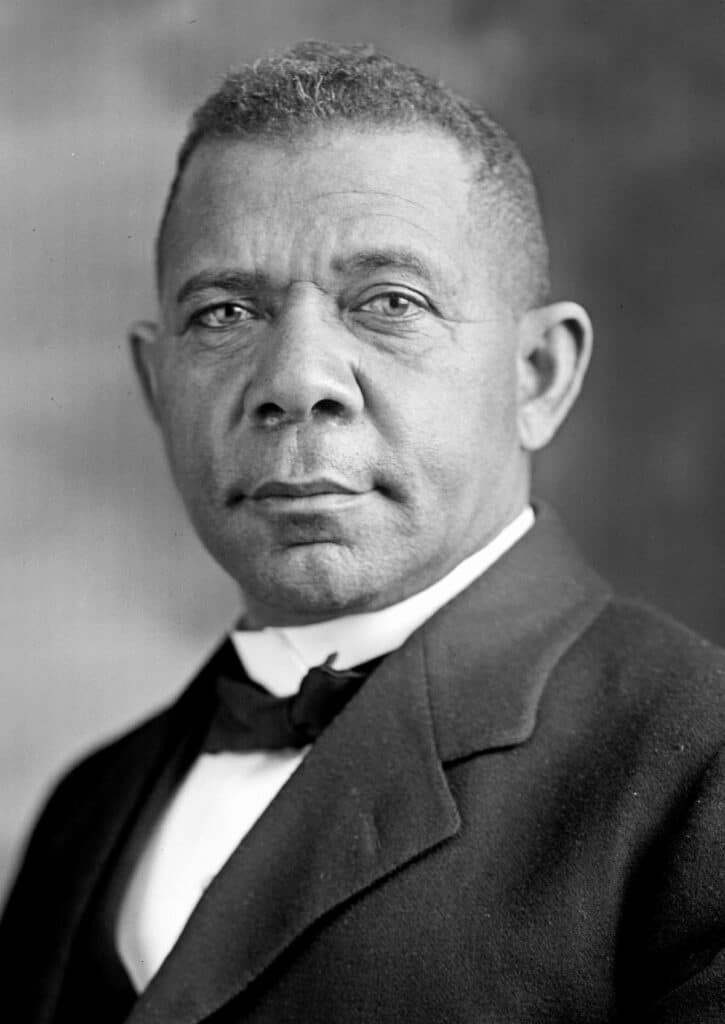

The war had left the South angry and poor and the North rich and beneficent. If one wanted to do something in the South, one needed to go North to find the money, and Boston was a key venue. Thus, entrepreneurial and visionary activists like Booker T. Washington, principal of Tuskegee, scheduled numerous trips for himself and others from his school to speak in Boston and cultivate financial support. By the 1890s, a large number of philanthropic individuals and institutions viewed Tuskegee as a successful model for education in the South. In the school’s early history Trinity’s Rectors were among the northerners who sat on the school’s board.

Donald believed strongly in supporting southern education for Blacks. On Sunday December 3, 1893, Trinity Church hosted a gathering to raise interest and funds for Tuskegee. Donald, in his introduction, said, “The Tuskegee institution is to help those men whose ancestors we enslaved. The North owes them a debt, on the ground of political economy. The South lost money by slavery; it impoverished her while it made the North rich. We should listen to Mr. Washington as a man who can tell us how best to repair the damage we, through our ancestors, have done.”

Donald, along with other Trinity parish leaders with the same goals, like Sarah Wyman Whitman, Charles E. Mason, and Robert Treat Paine organized gatherings at Trinity in support of these and other Black schools like Atlanta University. Donald was also a frequent speaker on the topic at neighboring institutions like Old South Church. When a service was held at Old South Church in the interests of Fisk University located in Nashville, Tennessee, Donald attended and endorsed the work of the school and its president on behalf of Black youth.

In 1895 Donald delivered the commencement address at Tuskegee. In his autobiography, Up From Slavery, Booker T. Washington recounts, “At one of our Commencements I was bold enough to invite Rev. E. Winchester Donald, D. D., rector of Trinity Church, Boston, to preach the Commencement sermon. As we then had no room large enough to accommodate all who would be present, the place of meeting was under a large improvised arbour … Soon after Dr. Donald had begun speaking, the rain came down in torrents, and he had to stop, while someone held an umbrella over him. The boldness of what I had done never dawned upon me until I saw the picture made by the rector of Trinity Church standing before that large audience under an old umbrella. … After he had gone to his room, and had gotten the wet threads of his clothes dry, Dr. Donald ventured the remark that a large chapel at Tuskegee would not be out of place. The next day a letter came from two [Northern] ladies who were then travelling in Italy, saying that they had decided to give us the money for such a chapel as we needed.” In that same year Donald established the Trinity Church Oratorical Prize, an award for the best written and best delivered paper on an assigned subject, a student prize that continues at Tuskegee, with different sources of funding, to this day.

Donald and Washington developed a close relationship. In 1897, Washington was invited to deliver an address at the dedication of the Robert Gould Shaw Monument in Boston. Prior to his arrival, Donald sent him a letter. “I hope to see you on the occasion of your visit to Boston to make the address on the unveiling of Shaw’s monument. I told St. Gaudens the other day that he would better understand his long delay in finishing the Shaw statue when he should have heard you speak; and that he will then understand that Divine Providence stayed his hand in the execution of his task until you should be full grown and come to your prime as an orator. After your oration, I shall ask St. Gaudens whether he does not think I told him the truth. With love to Mrs. Washington and the children, I am Ever sincerely yours.”

Until the end of his days, in person and in writing, Donald would support the efforts of Washington at Tuskegee and those at other Southern Black schools educating new generations. He supported the efforts of many people inside the U.S. and from abroad trying to make social change. He may have thought he was being militant.

When Donald wanted to host a gathering in support of Berea College in Kentucky with Theodore Roosevelt as speaker, there was resistance. Donald, being strategic, went to longtime vestryman Robert Treat Paine and Paine is remembered as saying, in effect, “When Trinity becomes too good to host such an event, may lightning strike and burn it to the ground.” The meeting took place.

In 1901 Donald delivered a dedication address at Tuskegee for a new building. During the address, Donald would say: “We are in the presence of a fact. Whether or not the negro can be raised to self-respect, industry, thrift and ethical soundness, let the doctrinaires debate. One thing we know, whereas he was blind to his only chance, now he sees. He has only to keep his eyes open and use his chance to rise clean out of the condition into which 200 years of enforced servitude and thirty-five years of stupid, selfish and merciless political exploitation thrust him down.” His words were controversial to some with statements including “an educated negro without a vote is worth infinitely more than ten illiterate white men who vote as often as the polls are open.”

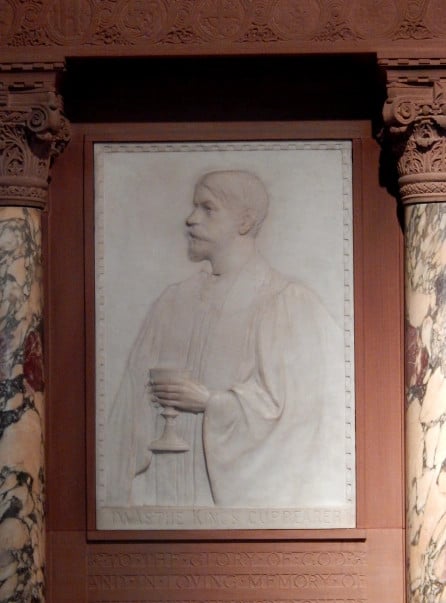

Donald died in 1904 after a long battle with tuberculosis. His funeral took place at Trinity Church on November 20. The Reverend William R. Huntington of Grace Church NY delivered the eulogy, opening with scripture from Nehemiah: I am the King’s cupbearer. Huntington goes on to describe the symbolism of the cup in the Old and New Testaments, and how to be the bearer of the King’s cup is honorable, a blessing.

“Dr. Donald your late rector, Winchester Donald your friend and my friend was thus privileged. He was King’s cup-bearer. … It is a great thing to be a preacher of righteousness. He was that. It is an even greater thing to be a son of consolation. He was that also. How often men mistake their own powers and misinterpret their own gifts! Had you asked your late minister to define himself, he most likely would have said, “I am a swordsman. I fight the King’s battles.” But no, his supreme gift was not militancy, – however it may have seemed to some, as well as to himself, – his supreme gift was not militancy, it was sympathy; he gave drink to the thirsty; he satisfied the longing soul; his true emblem was not the claymore, as he fancied, it was the chalice.”

Elijah Winchester Donald’s memorial, located in the south transept of Trinity Church, was unveiled January 27, 1907. In a setting designed by his friend Charles A. Coolidge, the bas relief by sculptor Bela Pratt depicts Donald in profile and in his hands, he holds a chalice.

Until next time,

Cynthia

Sources and Further Reading

Books and Pamphlets

- The King’s Cup Bearer: A Sermon in Memory of Rev. E. Winchester Donald by Rev. William R. Huntington

- Up From Slavery by Booker T. Washington

Newspapers

- Andover Story “When Andover Went Underground”

- Boston Herald Monday December 4, 1893. “Seeking Help for Tuskegees. Mr. Booker T. Washington Speaks at Trinity Chapel.”

- Boston Evening Transcript Wednesday June 5, 1895. “Dr. Donald to the Negroes. The Rector of Trinity’s Baccalaureate Sermon at the Tuskegee Institute, Alabama.”

- Boston Globe Tuesday December 1, 1896. “Education their Need. Pleas Made for Mountaineers of Kentucky.”

- Boston Herald Monday December 9, 1901. “Service in the Interest of Fisk University.”

Colleges and Universities Cited