“There are but a few Japanese in Boston, not over 80, and of these only one fourth are here for the purposes of education. The remainder are butlers, servants and small tradesmen.”

Boston Post Sun, 1904

Dear Trinity Church and friends,

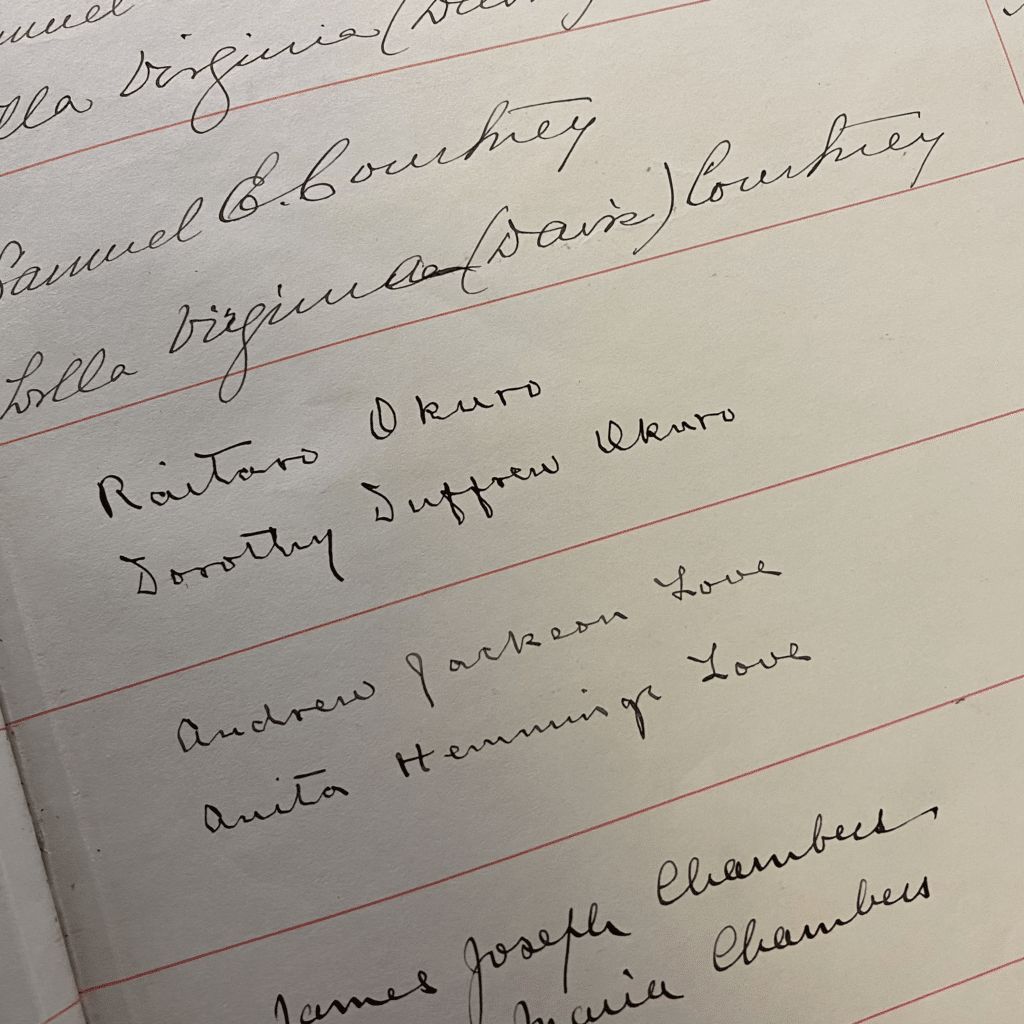

Raitoro Okuro straddled many of these worlds while in Boston. I chanced upon his name while looking through a Trinity Church Baptism Book covering the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It is a hefty tome recording the names of those baptized, their dates of birth, parents, and sponsors. Okuro’s son, Raitaro Arnold Okuro, was born in 1905 and baptized at Trinity that same year. Later in his life, he would be known as Arnold R. Okuro. In beautiful calligraphic script, his parents are identified as Raitaro and Dorothy Duffieu Okuro. Charlotte E Arnold, Masanori Osaki, a visiting student at Hobart College, and Shintaro Morimoto served as baptismal sponsors. Morimoto was a well-known Japanese businessman leading the Boston branch of the firm Yamanaka & Co. located on Boylston St. At the time of Arnold R. Okuro’s baptism, Morimoto was considered the only Mason in New England of Japanese heritage.

Born in Hakodate, Japan in 1873, Raitaro Okuro emigrated in 1889 to study in New Brunswick, Canada at the Mount Allison Boy’s Academy. The student newspaper, The Argosy, noted that Okuro hoped to return to Japan as a missionary. In 1895 he left Mount Allison to study at the Boston School of Theology. By 1899, he was also employed as butler in the home of wealthy businessman Charles Bond at 128 Commonwealth Avenue. It was at 128 Commonwealth that Raitaro Okuro met and fell in love with Dorothy Duffieu, the family’s live-in English governess.

The two were married in 1903 in the West Somerville home of manufacturer Albert B. Bent. Their marriage was noted in the Boston Globe. The ceremony was performed by Reverend Arthur Page Sharp. The bride was gowned in white silk and wore a veil of rare old lace. Later that same year, as the Russo-Japanese War loomed, the Boston Sunday Globe put forth the question: What is the destiny and mission of Japan? Answers were sought from the following men, considered representative Japanese: Barnabas S. Kimura, a student at the Episcopal Theological School; R. Hirose; Bunkio Matsuki, a Japanese art dealer with a gallery on Boylston Street; and Raitaro Okuro.

Okuro ends his column with the following words:

“… Indeed, a more fortunate opportunity than today cannot be hoped for, for we have at our command now ample means of achieving a victory over our rival. Therefore we must make determined demand for the withdrawal of Russian troops [from China] and we should not allow ourselves to be deceived by the Russian diplomacy. We must push on with all our might and main till the Manchurian difficulty shall be settled. “

Less than a year later, on February 8, 1904, Japan launched a surprise attack against Russian forces anchored off the coast of Port Arthur, Manchuria. The Russo-Japanese War had begun. It continued until September 1905 when President Theodore Roosevelt negotiated a peace, an act for which he would receive the Nobel Peace Prize in 1910.

Though it does not appear that Okuro returned to Japan as a missionary, he was a leader among the Japanese community in Boston. A 1904 Boston Herald article notes that “Almost every seat in the Every Day Church, Shawmut Avenue, was taken last evening at the unique Japanese entertainment given by T. Togi and other members of the Japanese colony in this city. The programming consisted of songs, sword dances, readings and instrumental selections.” At this event, Okuro was invited to give a short talk on relations between nations. At the 1906 gathering in celebration of the Mikado’s (Japan’s emperor) birthday, Okuro was designated toastmaster to replace Bunkio Matsuki who was delayed in returning from Japan. In attendance were Japanese citizens and merchants in Boston and students from the colleges and technical schools.

While remaining civically involved, Okuro continued to work as a butler. By the time his son Arnold was fifteen years old, records indicate that Okuro, now a widower, his wife having died in England in 1917, was living in North Reading, Massachusetts. Okuro worked as a bacteriologist at the North Reading State Sanitorium for tuberculosis patients where he had formerly been a patient.

Raitaro Okuro died in 1922 and is buried in the Riverside Cemetery in North Reading. While Raitaro was ill, his son, Arnold, lodged in the home of Constantine and Alice Tutein. Arnold would eventually marry the Tuteins’ daughter, Dora. In the 1920s, he attended the Northeastern Automotive School. In 1930, he and Dora wed, and census data indicates he was employed as a mechanic in a garage. His 1940s World War II draft card indicates that he and Dora lived for a time in West Roxbury and that he worked as an instructor at the Franklin Union Technical Institute. Now known as Franklin Cummings Tech, the school first opened its doors in 1908. Okuro instructed Coast Guard and Navy submarine students. In 1952 he moved on from the school and found Automotive Marine, Inc of Osterville, MA from which he retired in 1972. Over six decades after having been baptized at Trinity Church, Arnold Raitaro Okuro died at the age of 68.

Until next month,

Cynthia

Sources and Further Reading

- The Argosy student newspaper, January 1891, Volume XX, p.59.

- “What is the Mission and Destiny of Japan,” The Boston Globe Sunday October 25, 1903

- “Mikado’s Birthday Saturday,” Boston Evening Transcript, Friday November 2, 1906

- Annual Report of the Trustees of Massachusetts Hospitals for Consumptives, 1919

- Franklin Cummings Tech https://franklincummings.edu/about-us/mission-and-values/

- “Arnold Okuro, Submarine Instructor,” Boston Herald September 19, 1973

- Mount Allison University Firsts https://libraryguides.mta.ca/firsts/raitaro_okuro

- Photo source: Mount Allison University Archives – 2007.07/252