Dear Trinity Church and friends,

Imagine, if you will, June 22, 1898, as the bride made her way down the aisle of Trinity Church. She wore ivory white trimmed with orange blossoms. Upon her head, a long white veil of tulle caught in her hair with a coronet of orange blossoms. In her hands, a bouquet of white roses. The church was well-filled that night as reported by the Boston Globe. The wedding was a fashionable affair of Boston’s Black elite. At the chancel railing, the bride was met by the groom, Dr. Marcus Wheatland and his best man, Lyde W. Benjamin. Officiating was the Reverend E. Winchester Donald. The bride’s name was Cordelia Irene DeMortie. Cordelia was the daughter of Mark R. DeMortie, who was described by the Globe as “a well-known leading colored man and merchant of this city.” He was that and much more.

“I was born in Norfolk, Virginia May 8, 1829,” he shared in an autobiographical sketch. “At the age of 18 I became acquainted with a man known as “Dr.” Harry Lundy who was an unlearned man. He took me into his confidence and told me that he was accustomed to conceal slaves in his house prior to their being run away from slavery. … He would have me write letters to parties with whom he cooperated. From that time until the age of twenty-two, I had assisted and caused the escape of about twenty-two slaves to Dr. Tobias at Philadelphia and others to New Bedford. … Men I would have stored away, one or two at a time in a vessel bound North paying the captain or steward $25 for each man. A woman I had to pay $50 because she had to be dressed in man’s attire and they would only take one woman at a time; the slaves furnished their own money with one exception. Namely I came to Boston in 1851 and I met Mr. Lewis Hayden and had conversation with him in reference to slaves running away from the South. I said that many of them would come if they had the means. I mentioned one man to him that had been trying to save $25 for about a year but could not do so. In a few weeks when I was about to return to Norfolk Lewis Hayden gave me $25 to pay for that man’s freedom.”

When an enslaved person’s owner learned of DeMortie’s actions, DeMortie recalled, “I had to resort to the same means to make my own escape. … I then came to Boston and opened a shoe store … There was an effort made to have me returned South as a fugitive from justice but Governor Clifford would not acknowledge property in slaves.” Told to arm himself with a pistol for safety as he went about his business, DeMortie mused, “that it would be better to be tried in Massachusetts for murder than to be tried in Virginia for running away slaves.”

DeMortie was politically active in Boston. Along with Black leaders like Lewis Hayden, he fought for desegregated schools. At the time, all Black children attended one school in Boston regardless of where they lived. In 1855, the legislature finally passed a bill requiring all children to attend schools in the wards in which they lived. In 1854, following passage of the Fugitive Slave Act, which legalized the capture of the formerly enslaved in the North for return to their owners in the South, DeMortie was part of an integrated group of Boston citizens who physically tried to prevent the return of formerly enslaved Anthony Burns. They failed, though their efforts further galvanized New England abolitionists.

As a labor activist DeMortie worked with Benjamin F. Roberts to change hiring practices for Black men. He worked with Roberts, Lewis Hayden, and others to have the word “col.” which implied “colored” removed from Black men’s names on the voting list. In 1863, he was asked to accept an appointment as sutler, the merchant that accompanies and meets the needs of a regiment. He agreed, and in April of that year, Colonel Robert Gould Shaw appointed him to that position for the 54th Regiment. After the war, he returned briefly to Boston before following entrepreneurial pursuits in Chicago and Virginia. Along the way, he married Cordelia Downing, daughter of George T. Downing, a successful Black businessman and noted abolitionist.

In 1887, the family returned home to Boston. Eleven years later he walked his daughter Cordelia down the aisle of Trinity Church.

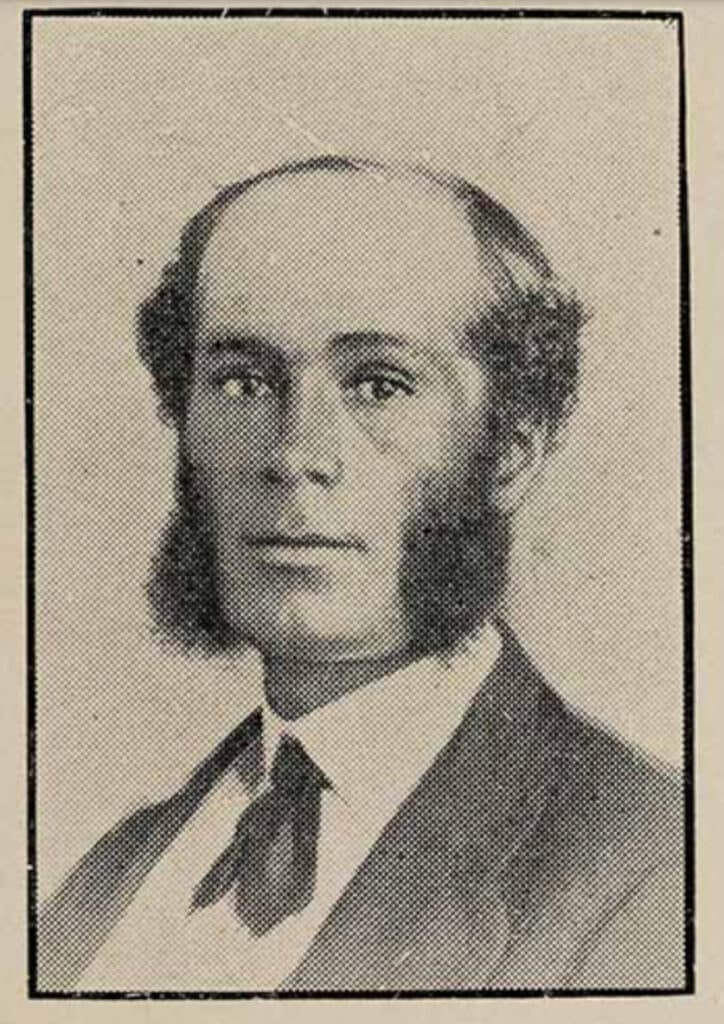

In her 1916 series in New Era Magazine, author Pauline Hopkins chronicled the lives of Black men who, through their achievements, demonstrated that they were “Men of Vision.” Hopkins selected DeMortie as number one on her list. She described DeMortie as a man of distinct individuality, great wit, who raised himself to power and wealth through character alone.

DeMortie played an important role in transforming the lives of Black people in Boston and beyond. Eventually he and his wife settled down to live with their daughter Cordelia in Newport, RI. There he died in 1914. He was buried at Woodlawn Cemetery in Everett, MA.

Until next month,

Cynthia

Sources and Further Reading

https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/demortie-mark-1829-1914/

New Era Magazine https://www.paulinehopkinssociety.org/new-era-magazine/