- Education Forums

Jesus on the Cross: Paradox of Glory; Mystery of Resurrection: Fish Fry on the Beach (John 17-21)

Related Forum Video

Memory Verse

“And Peter said to him, ‘Lord, you know everything; you know that I love you.’ Jesus said to him, ‘Feed my sheep.” – John 21:17

Reflection

Jesus on the Cross: Paradox of Glory – John 17-19

Many scholars believe that the Gospels were written from back to front, which is to say, that the core of the original proclamations about Jesus centered on his death and resurrection, and that the rest of the Gospels were built looking backwards from stories about those signal events: the ending and beginning again of his life. The synoptic Gospels (Mark, Matthew, and Luke) tend to focus their accounts of Jesus’ death and resurrection on the suffering of Jesus on the cross, and the redeeming of that suffering in the resurrection.

But John’s Gospel understands Jesus’ death and resurrection differently, and so tells the story differently. For John, there is no real separation between the cross and the resurrection. In this Gospel the entire sweep of the story—from Jesus’ being betrayed and arrested in the Garden of Gethsemane through the crucifixion itself, and on into the stories of resurrection—is one of great drama of glory paradoxically revealed.

As the Last Supper is ending, in Chapter 17, Jesus beings to speak clearly of the glory that has been revealed throughout his ministry—think of the signs (miracles) and the “I AM’ proclamations as each having revealed something of God’s glory—and that will now be revealed in his death and resurrection as well. After Jesus had spoken these words, he looked up to heaven and said, “Father, the hour has come; glorify your Son so that the Son may glorify you, 2since you have given him authority over all people, to give eternal life to all whom you have given him. 3And this is eternal life, that they may know you, the only true God, and Jesus Christ whom you have sent. 4I glorified you on earth by finishing the work that you gave me to do. 5So now, Father, glorify me in your own presence with the glory that I had in your presence before the world existed.

But what does the Jesus of John’s Gospel mean by this word glory? How can there be glory in suffering and death? As in so much of the New Testament, there is a Hebrew Bible background to this word, and its meaning. In the Bible that Jesus knew, the visible but mysterious signs of God’s presence are often referred to as “God’s glory.” The pyrotechnics when God appears to Moses on Sinai, the pillars of cloud and fire in the desert journey of the Hebrew people trekking from slavery to freedom, and the cloud of glory during sacrifices in the Temple in Jerusalem—all of these experiences of glory simultaneously reveal and shroud the presence of God. I myself have sometimes thought that a good image for the divine glory is the blinding light of bright headlights reflecting off fog. The light off fog simultaneously reveals and blinds—a true paradox.

And so it is with Jesus’ cross and resurrection—the glory of God is being revealed paradoxically. One needs to look closely, more deeply than a first-surface-glance, to see the glory of God revealed in Jesus’ dying and rising. This theme of the paradox of God’s glory—God’s mysterious blinding light—has been present since the opening words in Chapter One of John’s Gospel.In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. 2He was in the beginning with God. 3All things came into being through him, and without him not one thing came into being. What has come into being 4in him was life, and the life was the light of all people. 5The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness did not overcome it.

This glory that is being revealed in Jesus’ dying and rising is—at its heart—the glory of the love of God. The love that shines in the darkness and that darkness cannot overcome. The love that the pre-existent Christ and the Father have shared since before creation, and which was the overflowing love by which they brought all things into being. The love that Jesus came to proclaim and embody so that the love he and the Father share might become the love known to all who know Jesus, and through him come to know and love the God whom Jesus calls, Abba, Papa, Father. This love, this glory, is not Jesus’ possession alone, but through him becomes ours. As Jesus says in Chapter 17 of John, 22The glory that you have given me I have given them, so that they may be one, as we are one, 23I in them and you in me, that they may become completely one, so that the world may know that you have sent me and have loved them even as you have loved me.

The paradox of Jesus’ death being a source of light may be hard to see and understand at first. But one way to understand this more fully may be to look at a term for Jesus that is singular to John’s Gospel. It is only in John’s Gospel that Jesus is called “lamb of God.”(see 1:29 and 1:36). For any Jew reading or hearing John’s Gospel, only one image would have come to mind when hearing Jesus called “lamb of God,” and that image was of the twice-daily sacrifice of an unblemished male lamb in the Temple at 9 a.m. and 3 p.m. That Jesus was crucified and died at 3 p.m., and was called “lamb of God,”would have suggested to any Jew that Jesus has become the sacrifice offered to God. And there is some evidence that the prayers being offered in the Temple at 3 p.m. as that lamb was sacrificed revolved around four topics. God was begged to: (1) be our Redeemer; (2) forgive our sins; (3) send the Messiah; and (4) revive the dead. In this way, then, Jesus’ death as a lamb of sacrifice could be understood as glorious in that he became the means of redemption, the means of forgiveness of sins, the expected Messiah, and the one who would be the first fruits of the reviving of the dead. All four of these are glory-filled signs of divine love—redemption, forgiveness, messianic hope, and the beginning of resurrection.

And one last thing: Christian tradition has come to assert that by his death at the hour of sacrifice, Jesus—as God’s perfect lamb—has put an end to all sacrifice, solidifying forever the loving relationship between God’s people and the Holy One. No more sacrifice of animals is needed. But far more importantly, with Jesus the “full and final sacrifice” has been made, so that we no longer need to approach or relate to God as an angry God who needs to be propitiated by sacrificial actions on our part. This casts a particular kind of light on what Jesus meant in his last words from the cross in John’s Gospel: “It is finished.” (John 19:30) Jesus has finished the work of love. Jesus has finished all the sacrifice that ever needs to be made. It is done. Light has conquered darkness. Love has conquered hate. Life is about to conquer death. All that has been accomplished for us by God’s great love in Jesus. Our role is to believe in and trust in that love, and live our lives thankfully, not fearfully, using for the spreading of love and justice all the energy we might otherwise have dedicated to guilt, shame, and propitiation. If one comes to this understanding of Jesus’ death as the end of sacrifice, one can also extend this to conclude that the cross is God’s way of seeking to bring to an end forever the use of violence as a solution to any problem. If you would like to read more about this way of thinking, any of the works of René Girard would be of help, but particularly his “Violence and the Sacred.” One might also find it helpful to read, S. Mark Heim’s “Saved from Sacrifice: A Theology of the Cross.”

Mystery of Resurrection: Fish Fry on the Beach – John 20-21

Just as the cross is full of paradox—light in darkness, love conquering hate—so it is with the resurrection. One might have expected that the mystery would disappear in the coming of Easter morning’s new light and new life. Wouldn’t one expect that full light, full illumination would banish paradox and mystery? But that turns out not be so in the resurrection stories in John’s Gospel. The glory revealed in the resurrection is just as mysterious and paradoxical as the glory of the cross.

In this Gospel there are three major episodes that help unfold the mystery of new life that Jesus brings through his resurrection: Jesus appearing in the garden to Mary Magdalene; Jesus appearing to doubting Thomas; and Jesus appearing to Peter and six other disciples at a fish fry on the beach. In each of these stories there is mystery. In the misty light of early morning on Easter, Mary Magdalene does not recognize Jesus at first, mistaking him to be the gardener until she hears him call her by name. Thomas is absent when Jesus appears to his disciples on Easter night, and insists that he will not believe (trust) in Jesus and the resurrection until he can touch his Lord. And in the final resurrection appearance in John’s Gospel, Jesus appears in early morning on a beach to a cadre of the disciples (Peter among them) who have given up on spreading the word of resurrection, and have gone back to their “pre-Jesus” work as fishermen. It is as if John’s Gospel is saying: the light and life that Jesus brings are mysterious and full of surprises, not just in the cross, but also in the time of resurrection’s new life.

Each of these stories focuses on coming to believe despite the difficulties of trusting in Jesus’ resurrection. Our focus will be on the last of these stories: Jesus’ appearance to some of his disciples during a fish fry on the beach. Several things are particularly worth noting. First, despite the fact that Jesus has poured the breath of new and resurrected life into them and commissioned them to go on a mission of forgiveness (John 20:21-23), the seven disciples in this story have given up on that mission and have gone back to work as fishermen. That Jesus should come to them, despite their unfaithfulness to the mission for which he has commissioned them, speaks volumes about Jesus’ ongoing love and forgiveness of these less-than-perfect disciples. Second, they do not recognize Jesus at first, but simply see him as a stranger on the beach. We might understand this as the Gospel’s way of reminding us that Jesus appears to us in surprising people and circumstances, and that we may not—at first—recognize Jesus when he encounters us in others. Third, Jesus prepares a meal for them before they ever encounter him, and he invites them to bring some of the fish they have caught to add to the fish fry.

Perhaps we could understand this as a reminder that Jesus serves us before we ever join Jesus in his ministries of service, but that he always invites and welcomes the gifts that we bring—though they may be nothing more than small fry fish—to the meals he is placing before a hungry world. Fourth, Peter has not had a personal conversation with Jesus since Maundy Thursday night, when he denied Jesus three times. On the beach, Jesus has a tripartite heart-to-heart talk with Peter about love and service, as a counterweight to Peter’s tripartite denial. Despite Peter’s slowness fully to comprehend what Jesus is driving at in their conversation, Jesus demonstrates his own humble love and forgiveness for Peter—and his respect for Peter’s capacity to serve as shepherd, despite Peter’s denial and his lack of full understanding of Jesus’ love.

In this, we can see that Jesus’ heart is a forgiving one, and that his love for us is so deep, and his understanding of our weaknesses so full, that even when we turn away from him, or through word or action—like Peter—deny that we even know him, still he goes on loving and forgiving us. And most mysteriously and miraculously of all, despite all our foibles, Jesus still invites us to join him in shepherding and feeding others, thereby assuring us that the gifts we bring, however small or great, will be of use in his ministry to feed and shepherd the world into the kingdom of love and everlasting life that his God and Father has prepared for us and all the world to share in.

– Bill Rich

Poetry

"St. Thomas Didymus" by Denise Levertov (1923-1997)

In the hot street at noon I saw him

a small man

gray but vivid, standing forth

beyond the crowd’s buzzing

holding in desperate grip his shaking

teethgnashing son,

and thought him my brother.

I heard him cry out, weeping and speak

those words,

Lord, I believe, help thou

mine unbelief,

and knew him

my twin:

a man whose entire being

had knotted itself

into the one tightdrawn question,

Why,

why has this child lost his childhood in suffering,

why is this child who will soon be a man

tormented, torn, twisted?

Why is he cruelly punished

who has done nothing except be born?

The twin of my birth

was not so close

as that man I heard

say what my heart

sighed with each beat, my breath silently

cried in and out,

in and out.

After the healing,

he, with his wondering

newly peaceful boy, receded;

no one dwells on the gratitude, the astonished joy,

the swift

acceptance and forgetting.

I did not follow

to see their changed lives.

What I retained was the flash of kinship.

Despite all that I witnessed,

his question remained

my question, throbbed like a stealthy cancer,

known

only to doctor and patient. To others

I seemed well enough.

So it was that after Golgotha

my spirit in secret

lurched in the same convulsed writhings

that tore that child

before he was healed.

And after the empty tomb when they told me that He lived, had spoken to Magdalen,

told me

that though He had passed through the door like a ghost

He had breathed on them

the breath of a living man –

even then

when hope tried with a flutter of wings to lift me –

still, alone with myself,

my heavy cry was the same: Lord

I believe,

help thou mine unbelief.

I needed

blood to tell me the truth,

the touch

of blood. Even

my sight of the dark crust of it

round the nailholes

didn’t thrust its meaning all the way through

to that manifold knot in me

that willed to possess all knowledge,

refusing to loosen

unless that insistence won

the battle I fought with life.

But when my hand

led by His hand’s firm clasp

entered the unhealed wound,

my fingers encountering

rib-bone and pulsing heat,

what I felt was not

scalding pain, shame for my

obstinate need,

but light, light streaming

into me, over me, filling the room

as I had lived till then

in a cold cave, and now coming forth for the first time,

the knot that bound me unravelling, I witnessed

all things quicken to color, to form,

my question

not answered but given its part

in a vast unfolding design lit

by a risen sun.

Music

"St. John Passion" – Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

"Lo, the Full Final Sacrifice" – Gerald Finzi (1901-1956), with text by Richard Crashaw (1612-1649)

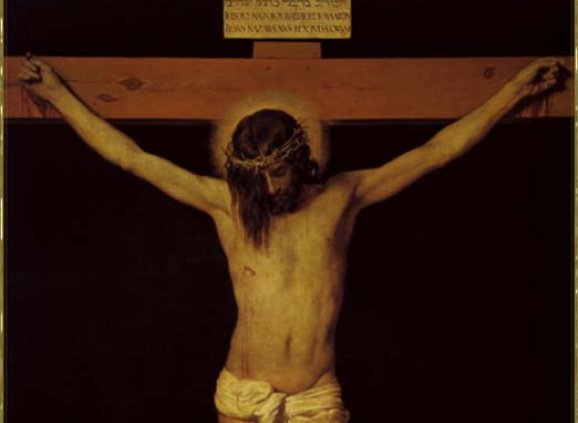

Art

“Christ Crucified” – Velázquez – 1632

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- July 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- October 2013

- September 2013

At "Educational Forums," enrich your spiritual journey by exploring our resources including videos of lectures, essays by priests, and other pieces about our faith, our church, and what it means to be a disciple of Jesus in the 21st century.

Comments