Dear Trinity Church and friends,

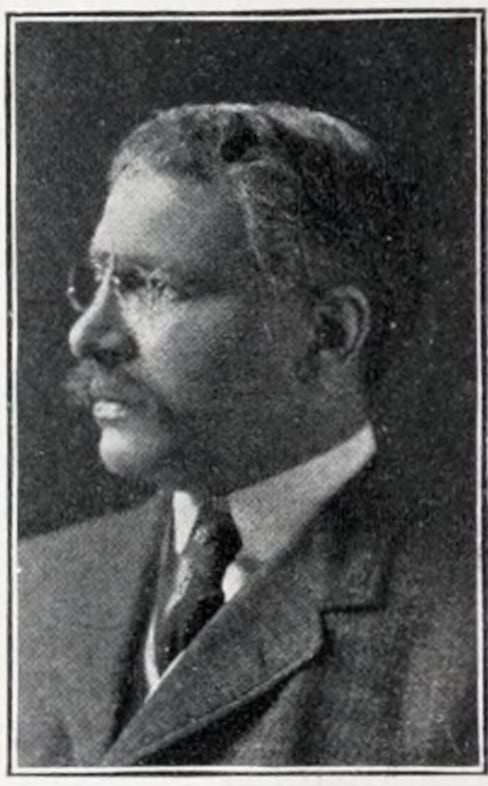

When Dr. Samuel E. Courtney wed Lilla Davis on October 21, 1896, at Trinity Church, according to the Boston Globe,”… it was an event of unusual importance both because of the high standing of the bride and groom and on account of this being the first public wedding of colored people to be celebrated in Trinity Church. Several hundred persons, the majority of them well-known whites, witnessed the ceremony … Dr. Courtney’s professional and political friends were present in large numbers.” Rector E. Winchester Donald officiated.

While Courtney had established a foothold in the Boston area decades before his marriage, he was originally from the South. Born around 1860 in Malden, West Virginia, he was the son of a wealthy white planter and his biracial enslaved servant. After the Civil War, he attended a local school staffed by a young Booker T. Washington. Washington recognized Courtney’s potential and encouraged him to continue his education at Washington’s own alma mater, Hampton Institute. Hampton was founded in 1868 as a place where Black students could receive post-secondary education to become teachers. Washington handpicked six students to attend the school. Courtney later recalled that they were collectively known as “Booker Washington’s boys.”

Courtney’s father, trained as a physician, paid for part of his son’s education while nurturing his interest in medicine. Courtney excelled in his studies and attracted the attention of Hampton supporter Horace S. Sears, a New Englander who’d made his fortune operating textile mills. After graduating from Hampton in 1879, at the invitation of Sears, Courtney moved to Weston, MA, to work and reside in the Sears household. He then began his studies in education at the Westfield Normal School in Westfield, MA. By the time of his graduation, his mentor and friend, Booker T. Washington, had assumed leadership of Tuskegee, a historically Black institution founded in 1881. In 1885, Washington employed Courtney to teach mathematics and drawing at the school.

Aware of the breadth and depth of Courtney’s New England connections, Washington also enlisted him as his northern agent, spreading word of the school’s achievements and setting the stage for future philanthropic requests. Through the groundwork of Courtney and other Black elites, the Boston area would become a significant funding source for Washington. In addition to these duties, Courtney also co-taught several teacher institutes for southern educators.

In 1887, the Boston-based Journal of Education chronicled his travels: “Professor S. E. Courtney, teacher of mathematics at the Tuskegee (Ala) Normal School, has been spending three weeks hereabouts, visiting the Institute of Technology, Latin and English High Schools, and Girls’ High School; also schools in Haverhill, Lawrence, Lowell, and Gloucester. The public would be surprised could it know how much is being accomplished in these days by the visits of Eastern teachers West and Western and Southern teachers East and North. This interchange of visits, the study of methods, of observation, is doing much to harmonize, interest, and develop educational zeal.”

In 1888, Courtney left Tuskegee to attend Harvard Medical School, graduating in 1894 as the school’s second Black graduate. He interned at Boston City Hospital and served as House Physician at the Boston Lying-In Hospital. At his home in Boston’s South End, he opened what was to become a successful medical practice that served both white and Black clients. Even as his medical career took off, Courtney remained socially and politically active. He was elected along with Stanley Ruffin, son of Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, as the two “colored” alternates to the 1896 Republican National Convention. A Boston Globe article described the two men as “people to watch.”

The Massachusetts at-large delegation to the Republican National Convention included Senator Henry Cabot Lodge and future governors of Massachusetts, Lt. Governor W. Murray Crane, Curtis Guild, Jr., and Eben Sumner Draper. The convention occurred in St. Louis, Missouri, a place where, as one journalist noted, southern prejudice prevailed. “…when the leading hotel where quarters had been engaged learned that one of the Bay State men, Dr. S. E. Courtney of Boston, was of negro blood, it was suggested that his presence would not be desirable. Lt. Governor Crane met the issue with characteristic tact and firmness. He said to the hotel manager that if Doctor Courtney were called upon to leave the hotel, the Massachusetts delegation would go with him, an event not calculated to advantage anybody.” Courtney would be elected an alternate delegate once more in 1900.

In 1897, Courtney was elected at large for his first three-year term on the Boston School Committee. He would later serve a second three-year term. He also served as Vice President of the National Medical Association several times.

Courtney maintained a close relationship with Booker T. Washington, who often stayed with the Courtneys when he visited Boston. In 1900 Courtney’s home served as the site of the founding of Washington’s National Negro Business League, an organization formed to help Black businessmen and women network and share stories and strategies for success. Still in operation today, it is known as the National Business League. Courtney actively served on the Executive Committee for many years.

Courtney and his wife had six children, several of whom were baptized at Trinity Church. Horace S. Sears served as one of the baptismal sponsors, and Courtney named one of his sons after his benefactor and friend. The Courtney home was a gathering place for many in the Black and white community. It hosted individuals, both friends and family, like Courtney’s brother, Henry. Henry would also marry at Trinity Church. Samuel Courtney’s wife Lilla was a well-known educator in her own right and founder and first teacher at the Cotton Valley School, Fort Davis, AL, a successful institution of the American Missionary Institution. Both were deeply committed to “progress for the race,” to use the language of the day.

For decades, Courtney had been part of a Black vanguard seeking to advance economic and educational opportunities for Blacks. Much had been achieved, and the embrace and philanthropic support of wealthy, white Bostonians had been an important component. But by 1911 Courtney acknowledged that the times were changing. The welcome and largesse of an earlier generation was no more. The current younger generation, Courtney suggested in an interview, a generation born well after the Civil War and after the fervor of abolition, was more prejudiced, and had no special sympathy for Blacks as had their forefathers. Plus, the influx of unskilled, uneducated Blacks from the south only heightened prejudice.

Courtney and his family were not immune to that prejudice. In April 1919, his two sons, Samuel and Roger, sophomores attending the University of Maine, were attacked in their room by fellow students. They escaped but were tracked down then “tarred and feathered” with molasses and feathers from the school pillows. Brushed off as simply hazing by some, no one was ever charged.

During the 1920s Courtney lost several family members and good friends. In 1923, Horace Sears died. In 1924, at Trinity Church, Courtney’s sons ushered during the funeral of his friend Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin. Courtney served as one of the pallbearers. In 1926, his son Horace, a textile chemist, suffered a medical emergency and died suddenly at 27. In 1929, a funeral was held at Trinity for his oldest son, Samuel. His son Roger died in 1930, leaving behind a pregnant wife and a toddler named Horace Sears, whom Roger had presumably named after his deceased brother.

Courtney and his wife retired to Newton, MA. He died in 1941 at 81, considered, according to newspapers, as one of Boston’s most widely respected physicians. Funeral services were held at the Waterman Funeral Chapel, Kenmore Square, with Bishop Henry Knox Sherrill officiating. The burial was in Mt. Hope Cemetery, Mattapan. In 1989, Westfield State College opened the dorm Courtney Hall, named in honor of its prestigious graduate.

Until next month,

Cynthia

Sources and Further Reading

Alexander, Adele Logan. Homelands and Waterways: The American Journey of the Bond Family, 1846-1926. Knopf Double Day Publishing Group, 2007.

Boston Letter. Journal of Education, 1887-12-08, Volume 26 Issue 647, p.348.

“Davis-Courtney First Public Wedding of Colored People Celebrated in Trinity Church.” Boston Globe. Thursday, October 22, 1896. P. 5.

Fox, Stephen R. The Guardian of Boston: William Monroe Trotter. New York: Atheneum, 1970. p. 41-42.

Gatewood, Willard B. Aristocrats of Color: the Black Elite 1880-1920. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990.

Harlan, Louis R. Booker T. Washington Papers Volume 2: 1860-1889. University of Illinois Press, 1972. p. 289.

McGruder, Kevin. Philip Payton: The Father of Black Harlem. New York: Columbia University Press, 2021.

Miletsky, Zebulon Vance. Before Busing: A History of Boston’s Long Black Freedom Struggle.

University of North Carolina Press, 2022.

“Negroes in New England Have Excellent Opportunities to Acquire Education. But Business and Industrial Opportunities are Very Slight and They are Found in Menial Positions.” The Freeman. Saturday, December 23, 1911. Indianapolis, IN. Vol. 24, Issue 51, p. 11.

Obituary. The Boston Herald. Sunday, March 3, 1929. p. 21.

Obituary. The Newton Graphic, June 5, 1941, p. 5.

Sieber, Karen. “Red Summer Racial Violence Comes to Campus.” Clio: Your Guide to History. August 6, 2021. Accessed July 5, 2024. https://theclio.com/entry/128856

“The St. Louis Group.” Boston Daily Advertiser. Thursday, April 23, 1896, Vol 167, Issue 97, p. 8.

Writers’ Program of the Work Projects Administration in the State of Illinois. Cavalcade of the American Negro. Chicago: Diamond Jubilee Exposition Authority. 1940. p. 8.

Source of photo – Hartshorn, W. N. An Era of Progress and Promise, 1863-1910: the religious, moral and educational development of the American Negro since his emancipation. Boston: Priscilla Publishing Co. 1910.