- Education Forums

Jesus: Cosmic Christ (John 1-4)

Related Forum Video

Passages

Logos Prologue; The Cosmic Christ (John 1:1-14)

Wedding at Cana, Nicodemus at Night, and Woman at the Well at Noon (John 2, 3, 4)

Logos Prologue; The Cosmic Christ (John 1:1-14)

Welcome back to “Meeting Jesus Again for the First Time” after our Christmas break. Just before Christmas, in the last week of Advent, we looked at the two birth narratives about Jesus in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke, noting both their common themes and their distinct differences. And now we turn to the Gospel of John, and instead of a birth narrative that focuses on the human origins of Jesus, we find this Evangelist beginning with a very different story of Christ’s beginning. John’s Gospel begins with what has often been called the “Logos Prologue,” for it is centered on the cosmic origin of the Christ, God’s Word, or in Greek: the Logos of God.

In these 14 verses that introduce the coming into human flesh of God’s Word, or Logos, we find some of the deepest and most mysterious assertions about who Jesus the Christ really is, and what his origins were. At the center of these poetic reflections, we find the startling, mind-and-soul stretching assertion that what has come into being in Jesus is God’s eternal Word, a Word that has existed alongside God since before Creation began. It was through this Word that God brought all things into being, so that we begin to understand that the speaking-into-creation that God did in Genesis was not merely through words in the human sense, but through a living cosmic Word that is part of the very being of God. This Word—that God has been speaking since before time and forever—has now been incarnated in Jesus the Christ, has taken on our human flesh, and has come to live among us.

Actually the Greek for “lived among us” means “set up his tent” among us, and calls us to remember the God who lived among the Hebrew people in the tent of meeting as they journeyed from slavery in Egypt, through the wilderness, to their freedom and true home in the Land of Israel. In this way, the Evangelist pricks our memory to hint that the Word who comes into our flesh in Jesus will lead us from a different sort of bondage into a different land of freedom and delight.

But the Greek word Logos has many other nuances to it beyond the meaning of “Word,” and any reader of the Greek would have heard echoes of both Jewish reflections about the figure known as Wisdom (or Sophia), as well as echoes of Greco-Roman Stoic philosophy. For the Jewish reader, John’s use of the word Logos would have called to mind Jewish meditations on Wisdom (Sophia) as a feminine figure who worked together with God in the making of the world. To the student of Greco-Roman philosophy, the word Logos would have called to mind a number of philosophical concepts, including reason (implying that Jesus was the embodiment of reason), as well as structure/science (which could have been understood to imply that Jesus is the human embodiment of the way God engineered the entire universe).

To call Jesus the embodiment, the incarnation, of Logos then was a sweeping assertion that the deepest truth that human beings could search out—whether in Jewish or Greco-Roman philosophical reflections—was revealed in a single human being: Jesus. He was both human and time-bound, but also eternal and beyond all the bounds of time and space. To know him and to follow him, to believe in him, was to come to know and follow the deepest, most logical, sound and reliable truth that ever had been or ever would be. That all of this is asserted in these few verses of the opening of John’s Gospel sets up the entire thematic sweep of the Gospel, which will illustrate through story after story the way this Word, this Wisdom, this Light, this Truth lives, acts, loves, dies, and then lives anew beyond the bounds of death, space, and time.

Wedding at Cana, Nicodemus at Night, and Woman at the Well at Noon (John 2, 3, 4)

The stories that are at the heart of chapters three and four are particularly dear to us at Trinity. The John Lafarge murals that adorn the walls of the nave as we enter and leave the church depict these stories: the story of Nicodemus coming to visit Jesus at night (chapter three – on the south side of the nave) and the story of the woman at the well encountering Jesus at noon (chapter four – on the north side of the nave). The themes of both stories tie back to words in the Logos Prologue in which Jesus is described as the light that was the light of all people, light that darkness did not overcome. These two stories deal subtly with the theme of light and darkness.

Nicodemus is a “leader of the Jews,” implying that he is a member of the Sanhedrin, a sort of Supreme Court of the Jews. One would expect him to be as full of light as any good Jew could be, but it turns out that he finds it nearly impossible to understand what Jesus says to him, and is in effect “in the dark” about the truths that Jesus proclaims. He cannot seem to understand Jesus’ symbolic language about being born again from above, but gets stuck on a somewhat humorous picture of crawling back into the mother’s womb—the darkness—to come out into the light a second time. The light does not seem to dawn on him that Jesus is the bringer of divine light, and that the symbolic language Jesus uses is full of new light and the life that new light can bring for those with the eyes to see it, and the heart to take it in. For Jesus proclaims that the light he comes to bring is God’s love for the world in the famous verse of John 3:16, “For God so loved the world that he gave his only son so that all who believe in him may not perish but may have eternal life.” Buried in this symbolism is the idea that Jesus has come forth from the dark and unknown realm of divine mystery of love to bring light and life with him to any who have the eyes to walk into this new light instead of dwelling in the familiar darkness of the past.

In chapter four, Jesus encounters a woman that any Jew of his time would have considered to be “in the dark” about God. For she is a Samaritan woman, a heretic in the eyes of good and faithful Jews, worshiping God on the wrong mountain, and not accepting much of the Hebrew Scriptures as inspired by God. But this story, like that of Nicodemus, is full of surprises. Though the reader expects her to be “in the dark,” she meets Jesus in the blazing light of noonday, and after bantering with Jesus about her less-than-admired marital status, she turns out to be the first person to move so solidly into Jesus’ light as to have the courage to proclaim him as Messiah to an entire town. In fact, though this woman is never named in the Gospel, our Eastern Orthodox brothers and sisters in Christ have nicknamed her St. Photini, “the enlightened one,” a sort of Christian Buddah-figure. The Orthodox also refer to her as evangelist and apostle.

In a strange twist of misunderstanding and darkened hearts, many interpreters of this story in Western Christianity have obsessively focused on Photini’s marital status, reading into the story that she is a prostitute, or at least sexually promiscuous because of her many husbands, and the current “man who is not her husband” when she encounters Jesus. But in Judaism a woman could almost never divorce a man. So what seems more likely is that she was barren, and had been divorced by man after man when she could not provide any children. If this is so, then she was an abandoned woman, rejected by man after man, and shunned by the women of her town (else she would have come to the well at dawn, the usual time to draw water.) It is Jesus who becomes a sort of husband—bridegroom—to her, and he becomes an overflowing well, a womb of life for this woman whose womb had been like a dry well, and never been able to bear children. And by the light and life that wells up from him into her, and that she accepts from him, she becomes a different sort of mother, a spiritual mother, apostle and evangelist to all in the town who will receive the light and life she carries from Jesus to them.

- Bill Rich

Poetry

"Wedding Toast" by Richard Wilbur (1921-)

St. John tells how, at Cana's wedding feast,

The water-pots poured wine in such amount

That by his sober count

There were a hundred gallons at the least.

It made no earthly sense, unless to show

How whatsoever love elects to bless

Brims to a sweet excess

That can without depletion overflow.

Which is to say that what love sees is true;

That this world's fullness is not made but found.

Life hungers to abound

And pour its plenty out for such as you.

Now, if your loves will lend an ear to mine,

I toast you both, good son and dear new daughter.

May you not lack for water,

And may that water smack of Cana's wine.

Music

Jesus Met the Woman at the Well – Gospel song sung by Peter, Paul, Mary (1966)

Art

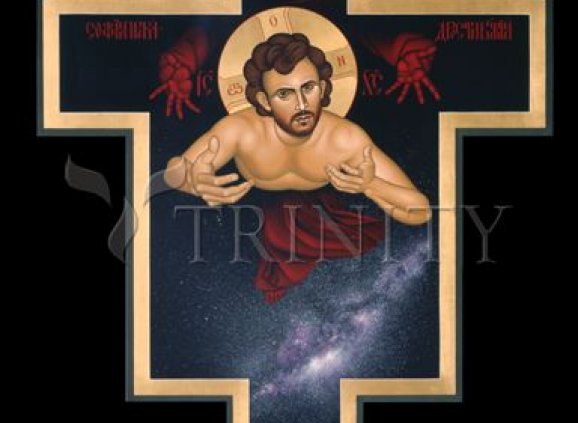

"Dance of Creation" – Icon written by Brother Robert Lentz, OFM (1946-) - See Above

Icon Writer’s Narrative:

This icon celebrates ancient Christian tradition and the most startling contemporary discoveries about the nature of the Cosmos.The transparent figure of Hagia Sophia (“Holy Wisdom”) dances and sings playfully in the background, true to her description in the Book of Proverbs. Her open hands scatter galaxies of stars and all they contain. In the foreground is the Logos, pattern of all creation, incarnate in the Cosmic Christ, celebrated in the Gospel of John and embraced by mystics throughout centuries. His extended hands order and gather back to the mystery all of creation which reaches its completion in him. The galaxy beneath Sophia’s feet is the Milky Way. The inscriptions name Jesus Christ and Sophia, Holy Wisdom of God, in Church Slavonic, the language of the Russian Church which has pondered these mysteries so deeply in times past. Scientists, today, tell us that in the creative vacuum that exists between the tiniest sub-atomic particles, elementary particles constantly foam into existence everywhere in the universe. The particles erupt in pairs: particles and anti-particles which annihilate each other. Certain particles called quarks continue to exist as they relate to each other, in groups of two or three, inter-dependently and inter-connectedly. Connectedness and interrelatedness are interwoven throughout the entire fabric of creation. The ground of the universe is absolutely dynamic and ever new as it constantly emerges and falls back into this all-nourishing abyss. The dance never ceases. A tradition dies when it stops growing. When it cannot expand to embrace new vistas, it should be discarded. We must find the ways in which our religion and science can dance together if we want a living spirituality. The mystery is too great to be grasped by any single approach.

- Brother Robert Lentz, OFM

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- July 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- October 2013

- September 2013

At "Educational Forums," enrich your spiritual journey by exploring our resources including videos of lectures, essays by priests, and other pieces about our faith, our church, and what it means to be a disciple of Jesus in the 21st century.

Comments